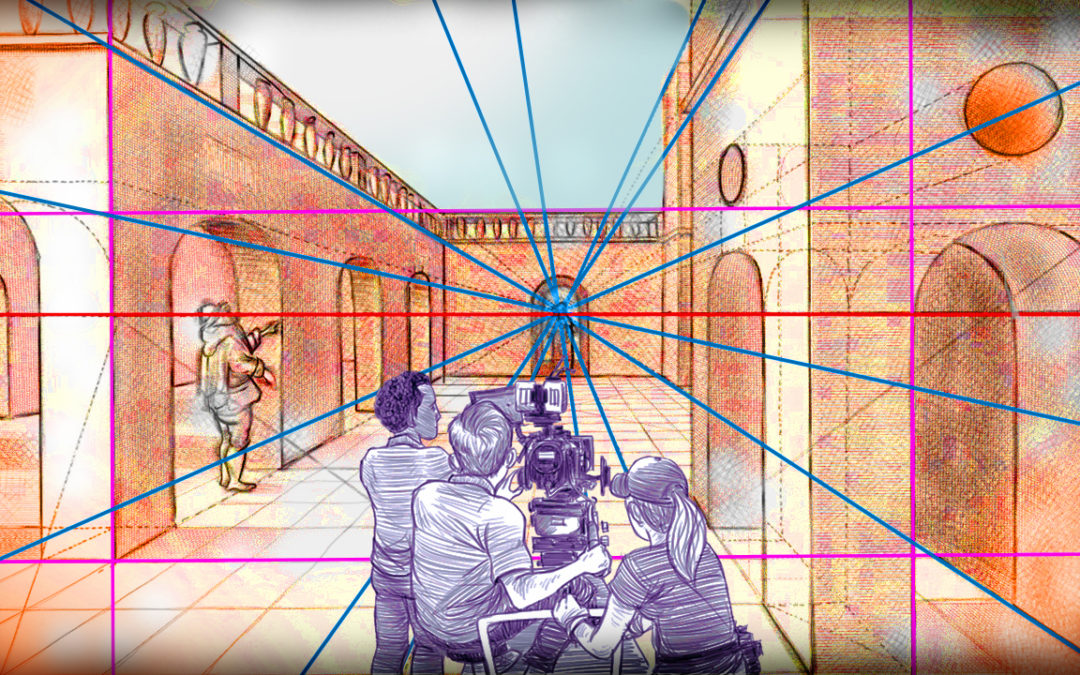

1. Push in

A basic dolly or zoom forward, the push in isolates the subject (be it an actor or a prop) from the world around them. This can be dramatic (from a wide to a close-up) or subtle (medium close-up to close-up). Use this technique to increase the intensity during a dramatic monologue, demonstrate the significance of a specific object in a scene, or convey deep thought or contemplation in a silent character.

From the famous restaurant assassination in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather to the climactic standoff in Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West, this technique has been used by some of cinema’s most brilliant auteurs. It was memorably employed to introduce the character Quint in Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, his size in the frame increasing to match his importance as he dominates the meeting with his brief monologue. Also notice the mirrored push in on Chief Brody, isolating these two characters in the crowded room, foreshadowing that their fates will eventually become intertwined.

2. Pull back

The opposite of the push in. Screenwriters will often employ the phrase “pull back to reveal…,” and that sums it up pretty well. Dollying or zooming out changes the audience’s perspective on your subject, revealing something new. It can create objectivity, contextualize the subject in the “world,” and often reveal an ironic juxtaposition. Use a rapid pull back for comedic effect, or a slower move to suggest the decay of trust or intimacy during a conversation. Pulling back can also reveal isolation or insignificance by making your subject much smaller in the frame.

Stanley Kubrick often used this technique, as in this scene from Barry Lyndon, where the protagonist is introduced in a medium shot before the camera pulls back to show him as just one small part of a great army. And Coppola used it to great effect in The Godfather’s iconic opening shot. As the undertaker tells his story, we slowly zoom out, gradually learning more information about his surroundings, eventually revealing the real focus of the film, Don Corleone, a silhouette who overshadows the smaller man.

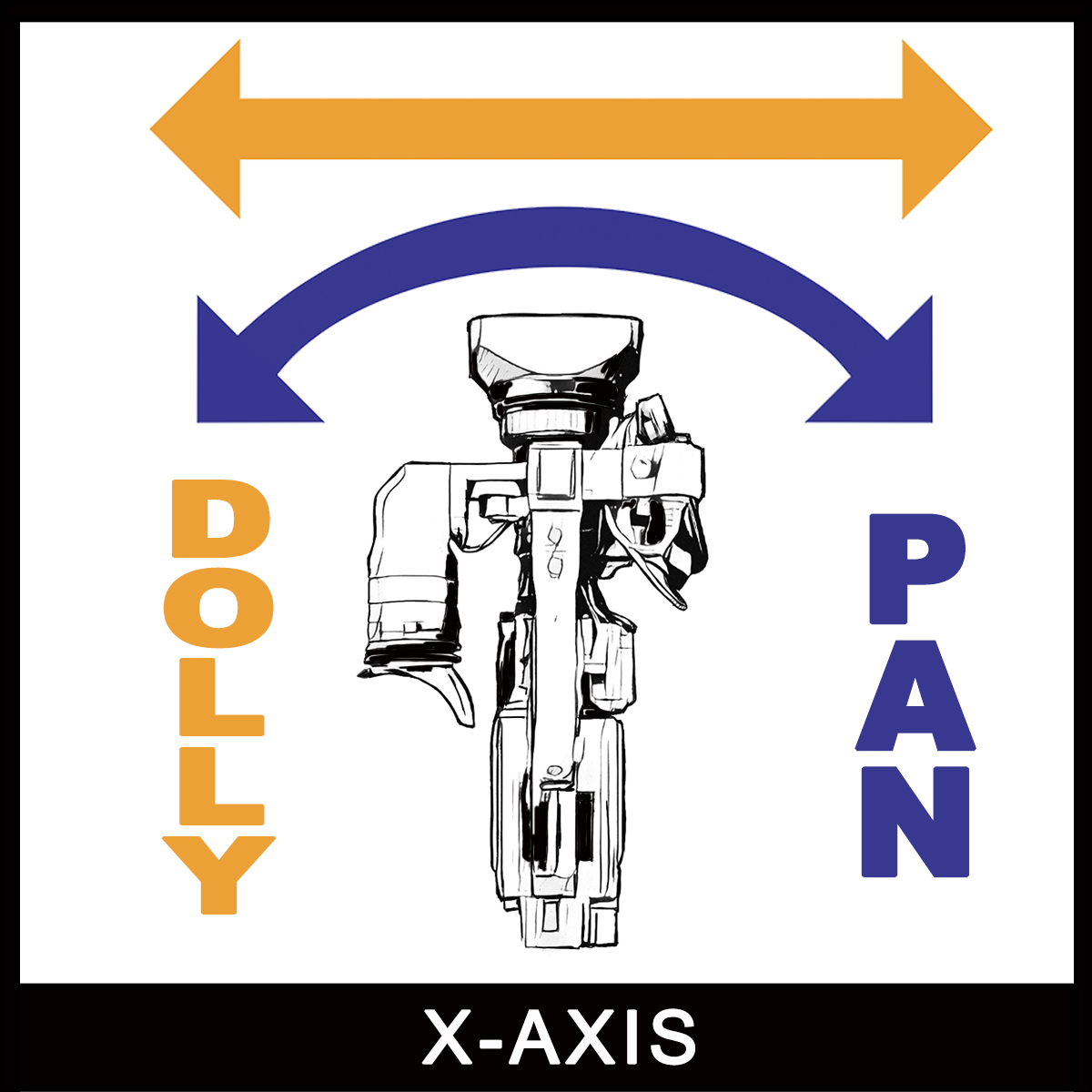

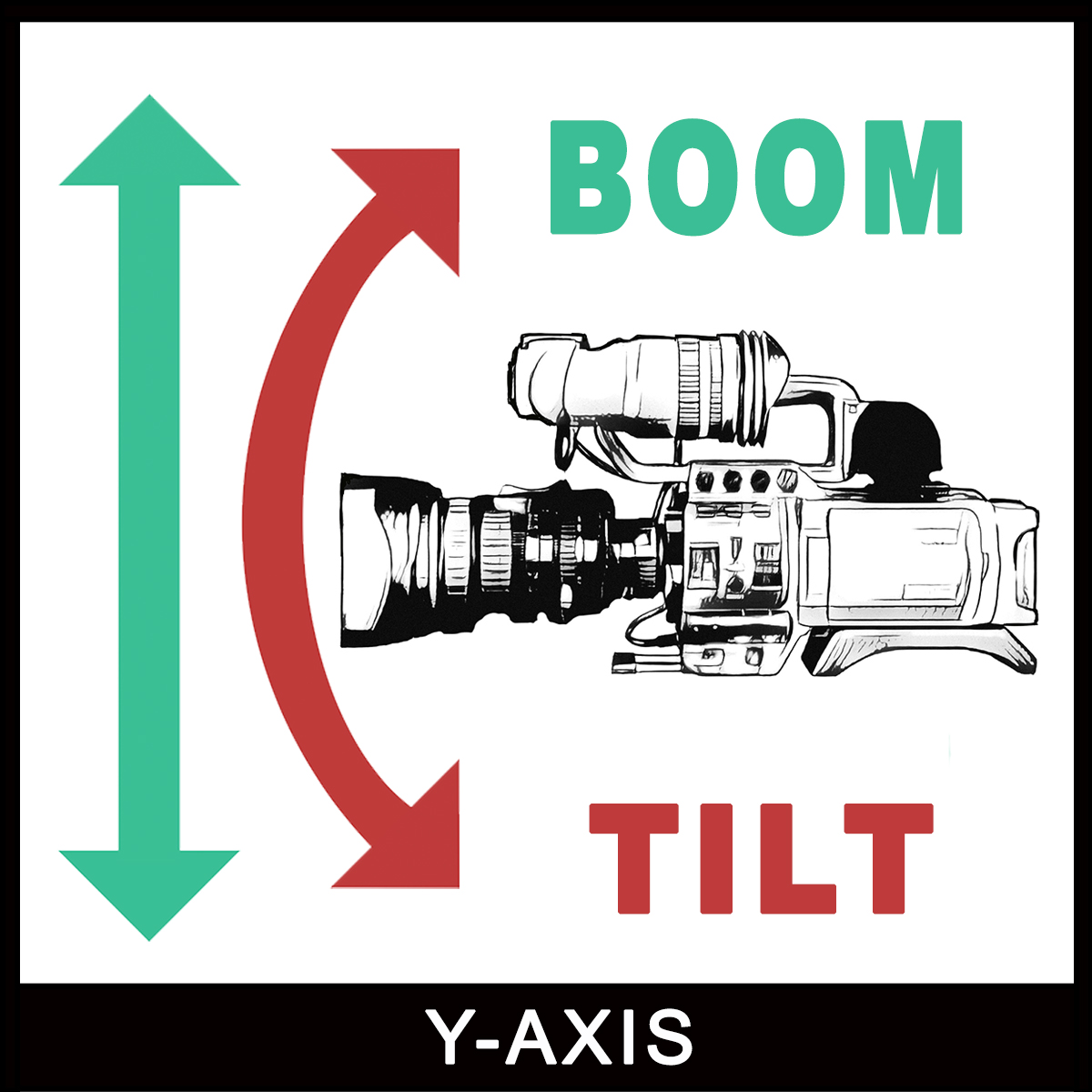

3. Tracking

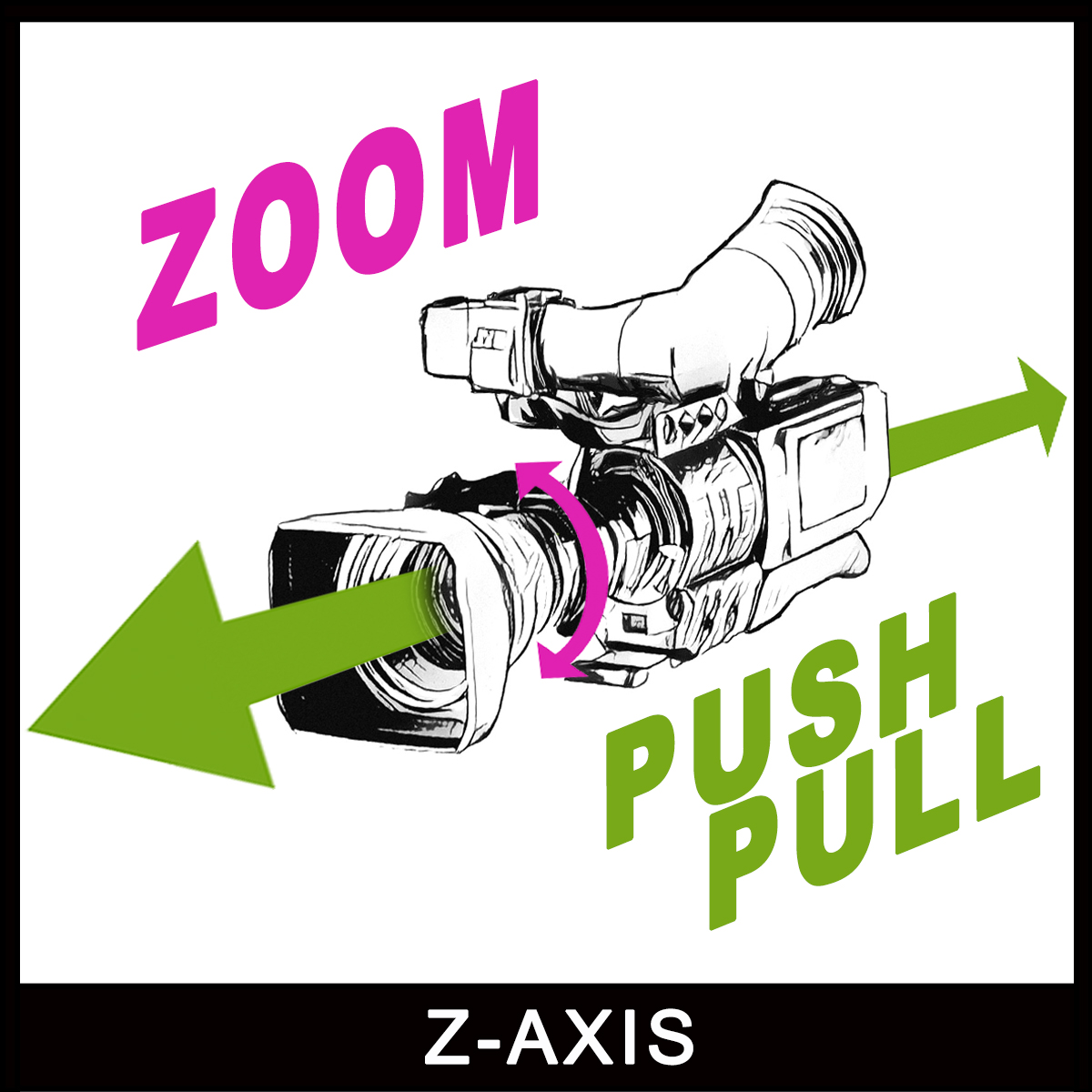

A tracking shot on the z-axis (handheld or on a dolly) moves forward or backward along with the subject. Use this technique to convey energy and forward momentum, or give a sense of the world the subject occupies. Tracking shots have been notably used by Martin Scorsese, Orson Welles, and Paul Thomas Anderson.

Kubrick frequently employed tracking shots to great effect in 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Shining, and in this early sequence from Paths of Glory where we track backwards through the French trenches of WWI, witnessing the callous General Broulard as he hurries through a perfunctory inspection of his beleaguered troops. Later, this walk is mirrored by the heroic Colonel Dax, only this time the reverse tracking shot is intercut with POV shots to convey Dax’s empathy.

4. Dolly/zoom

A.K.A. the “Vertigo-shot,” is when the camera is dollied in one direction while the lens is zoomed in the other, creating an otherworldly effect. Depending on which way you dolly/zoom this can make it feel as if the world is crowding in on your subject or dropping away from them. Use this technique to create a feeling of unease, discomfort, the warping of reality, panic, or a loss of control.

Alfred Hitchcock pioneered this technique and used it often, most memorably in Vertigo (of course). In Jaws, Spielberg used a dolly/zoom to accentuate a moment of horror, as Brody realizes the beachgoers are under attack. Scorsese used a very slow dolly/zoom in the critical diner scene in Goodfellas, when Henry Hill realizes that one of his oldest friends is going to betray him. Henry has his suspicions going into the meeting, but as he and Jimmy talk he realizes something just doesn’t feel right. The dolly/zoom helps convey that feeling to the audience on a more visceral level. The effect is subtle, as is the betrayal.

5. Snap zoom

Long out of fashion, this iconic technique of 70s filmmaking is currently experiencing a resurgence. The snap (or crash) zoom is a rapid, in-camera zoom, almost always used for a shocking moment, either subjectively, to represent the feeling of a character, or objectively, to stun the audience. It’s artificial and stylized, drawing attention to the filmmaking, but it is a bold and impactful technique that can be useful when you intend to be jarring.

Memorably employed by everyone from Mike Nichols to Sam Peckinpah, the snap zoom has staged a comeback thanks to retro-loving auteurs like Wes Anderson and Quentin Tarantino, and action oriented directors like Joss Whedon and JJ Abrams. But we’ll go with another example from Kubrick, master of every filmmaking tool in the toolkit. In The Shining he gave us one of the most memorable snap zooms, using it to accentuate a shocking moment (as if ghost/furry fellatio wasn’t shocking enough).